- Home

- Thornton, Brian

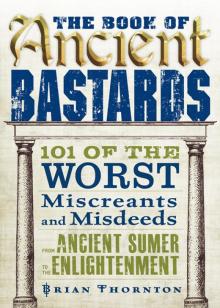

The Book of Ancient Bastards Page 5

The Book of Ancient Bastards Read online

Page 5

—Plutarch, Greek historian

Olympias was a princess of Epirus (modern Albania) whose father married her off young to Philip of Macedonia around the time Philip seized the throne. While it may not have been a love match, it was definitely a union between two extremely gifted, ambitious, and passionate people.

Doting on the son who ensured her power base at the Macedonian court (Alexander), Olympias grew cold toward her husband once it became clear that he had not the slightest interest in remaining faithful to her.

For her part, Olympias could be hard to take: tall, imposing, a force of nature with her temper and her strong will, she also made a point of creeping out the Macedonians with whom she came into contact, especially by playing up her status as a high priestess of an Epirot snake-worshipping cult. Soon she and Philip were barely speaking to each other, and Alexander, along with his younger sister Cleopatra (no, not that Cleopatra), was tugged back and forth between two very strong parental personalities.

Finally tiring of Olympias, Philip married a girl scarcely older than his own son, and soon got her pregnant with his child. When this new wife produced a baby boy, Olympias, Alexander, and many of their followers fled to her brother’s kingdom of Epirus, lying low there for nearly a year before Philip was assassinated in 336 B.C. With so much to gain from her husband’s death, and given her reputation for ruthlessness, it is beyond likely that Olympias had a hand in the plot that killed Philip.

What’s in a Bastard’s Name?

Originally named Myrtale, she took the regnal name of Olympias when her new husband’s chariot won an event at that year’s Olympic Games. Taking the name ensured that the honor of a Macedonian victory at the games would be celebrated for as long as people spoke her name.

The first thing Olympias did upon returning to the Macedonian capital of Pella was to have her rival and Philip’s new son killed, along with the girl’s father, a Macedonian nobleman who had set up the match hoping to inch closer to the throne and power himself. That wasn’t the end. Anyone who posed a threat to her son’s claim to the throne met with a quick and ruthless demise.

Within two years, the son on whom she so doted had gone to conquer Persia, never to return. Olympias was left at the Macedonian court, along with the general charged to run things in Alexander’s absence, Antipater. The two quickly grew to hate each other.

Once Alexander was dead, Olympias strove mightily to get his wife, his mistress, and both of the sons they had borne him (Olympias’s grandsons) safely home to Macedonia, where she could protect them and the dynasty. Olympias died for her cause, at one point invading Thrace (in the European part of Turkey) at the head of an army to try to free her captured grandchildren. When she lost in battle and fell into the hands of old Antipater’s son, she got what she had doled out to so many others: execution. She was killed in 316 B.C., and with this formidable barbarian queen out of the way, Alexander’s wife, mistress, and sons didn’t stand a chance. They were each in their turn quietly murdered.

18

PTOLEMY I SOTER

Sage Old Bastard Who Died in His Bed

(CA. 367–ca. 283 B.C.)

[Ptolemy] built a temple in honour of Alexander, in greatness and stateliness of structure becoming the glory and majesty of that king; and in this repository he laid the body, and honoured the exequies [funeral ceremonies] of the dead with sacrifices and magnificent shows, agreeable to the dignity of a demigod. Upon which account [Ptolemy] was deservedly honoured, not only by men, but by the gods themselves . . . . And the gods themselves, for his virtue, and kind obliging temper towards all, rescued him out of all his hazards and difficulties, which seemed insuperable.

—Diodorus Siculus, Sicilian Greek geographer and historian

The most successful of Alexander the Great’s successor-generals, Ptolemy I Soter (“Father”) succeeded because he was shrewd, calculating, and able to control the political narrative in an age when spin-doctoring was first coming into its own. We’re talking, of course, about the Hellenistic Age, the period that began with the death of Alexander the Great in Babylon (323 B.C.) and ended with the suicide of the last Hellenistic ruler, Cleopatra VII of Egypt, in 30 B.C.

During the three hundred years that make up the Hellenistic Age, a whole lot of ambitious and unscrupulous people (all of them related by blood in one way or another, frequently several times over) did a whole lot of awful things to each other, and all in the name of furthering their own political aims.

The seemingly inevitable wars that followed Alexander’s death are known collectively as the Wars of the Diadochoi (“Successors”). In dizzying progression, this ruthless pack of scoundrels picked each other off, the survivors of each round of violence circling each other, looking for an advantage, making and breaking alliances as it suited them.

That’s why the phrase “Hellenistic monarch” tends to be basically interchangeable with the word “bastard” for scholars who study the period.

Bastard Son, Bastard Brother?

Ptolemy is listed all over the historical narrative of the period as “Ptolemy, Son of Lagus.” No further mention is made of Lagus anywhere except this brief mention as Ptolemy’s father. His mother was a distant relative of the Macedonian royal house and the rumored one-time mistress of Philip, father of Alexander the Great. It is possible (perhaps even likely) that Ptolemy’s actual father was Philip himself, making Ptolemy Alexander’s bastard half-brother. This would help explain why a boy eleven years older than the young prince was listed as one of his childhood companions, and even went into exile with Alexander when the prince fled to Epirus shortly before the murder of his (their?) father.

When Ptolemy, childhood companion and advisor to the young Alexander, was offered a command as a royal governor in the aftermath of Alexander’s death, he chose Egypt: rich, fertile, both a breadbasket and a gold mine, easily defended because the deserts that surround it made travel across them by large military forces nearly impossible. From there, he ventured out to steal Alexander’s body from the caravan taking it home to Macedonia. This was a real political coup: control of Alexander’s body, to which he publicly paid every possible honor, gave Ptolemy the opportunity to set himself up as Alexander’s most legitimate successor. And this is what he did, for the most part settling back and allowing the successors to kill each other off for the next four decades.

Ptolemy’s greatest accomplishment wasn’t founding a dynasty that lasted for three centuries in Egypt, though. And it wasn’t writing a history of his famous king, used by countless historians during the next millennium (thereby allowing Ptolemy to by and large set the narrative of not just Alexander’s life story, but his own). His greatest accomplishment lay in doing what no other Diadochus managed to do: he died in bed, of old age. Truly a coup for a bastard in an age of bastardry!

19

PTOLEMY KERAUNOS

The Guy Who Made Oedipus Look Like a Boy Scout

(?–279 B.C.)

[T]hat violent, dangerous, and intensely ambitious man, Ptolemy Keraunos, the aptly named Thunderbolt.

—Peter Green, historian and Classics professor

In an age where the phrase “Hellenistic monarch” and “bastard” were interchangeable, one of the most notorious bastards on the scene was a prince who rebelled against his father, married his sister, murdered her children, and stole her kingdom. All this after stabbing a seventy-seven-year-old ally to death in a fit of rage.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet Ptolemy Keraunos (“Thunderbolt”).

The Thunderbolt’s father and namesake, Ptolemy I, has his own chapter in this book for a reason. But where the father was wily, the son was aggressive. Where the father plotted, the son acted.

In his eightieth year, with the question of succession pressing upon him, Ptolemy I gave up on his impulsive, hotheaded offspring. Instead, he chose a more sober half-brother (also confusingly bearing the name of Ptolemy) as his co-ruler and eventual successor.

Furious, Ptolemy Keraunos

fled to Thrace (in the European part of Turkey) and the court of one of his father’s rivals, Lysimachus. Ptolemy hoped to gain Lysimachus’s backing in a war with his father. Lysimachus put him off with vague promises, but did allow the younger man to stay at his court (possibly so he could keep an eye on him).

However, intrigue boiled over, and eventually Ptolemy left Thrace (moving quickly) with his sister Lysandra. They went to Babylon (in modern-day Iraq) to the court of Seleucus, by now the only other one of Alexander’s generals still left standing. Seleucus assured the two that he would support their bid for Lysimachus’s throne. (Lysimachus just happened to be an old rival of Seleucus’s.)

Seleucus’s forces triumphed in the resulting war. Ptolemy, who had fought on Seleucus’s side, demanded Lysimachus’s kingdom as Seleucus had agreed. And just as Lysimachus had, Seleucus put him off with vague promises.

Oops.

Enraged at having again been denied a throne he considered his by right, Ptolemy stabbed Seleucus to death, an act which earned him the nickname “Thunderbolt.”

Ptolemy then slipped out of Seleucus’s camp and went over to Lysimachus’s defeated army. Upon hearing that Ptolemy had killed the hated Seleucus, the soldiers promptly declared him Lysimachus’s successor and the new king of Macedonia. The only problem was that Lysicmachus’s wife Arsinoe (who happened to be Ptolemy’s half-sister) still held Cassandrea, the capital city of Macedonia. So Ptolemy struck a deal with her.

Bastard Marriages

Since the time of the pharaohs, dynastic marriage has been a political tool used by rulers to cement alliances and found dynasties. At no time was this practice more in fashion than during the Hellenistic period, when Alexander’s generals married the much-younger daughters of their rivals, and married off their own children to yet others of their rivals’ offspring. Such was the case at Lysimachus’s court: the old man himself was married to one of Ptolemy Keraunos’s sisters, a woman named Arsinoe, and another sister, Lysandra, was married to Lysimachus’s son and heir from a previous marriage, Agathocles. This is almost as confusing as all those Ptolemys, isn’t it?

Arsinoe agreed to marry Ptolemy, help strengthen his claim to the Macedonian throne, and share power as his queen. In return for this, Ptolemy agreed to adopt Arsinoe’s eldest son (also named, not surprisingly, Ptolemy) as his heir.

You can guess what happened next.

While Ptolemy was off consolidating his new holdings in southern Greece, Arsinoe began plotting against him. She intended to place her eldest son (the one named Ptolemy) on the throne and rule in his name.

Once again furious (it seems to have been his natural state), Ptolemy killed Arsinoe’s two younger sons. Arsinoe headed home for Egypt and the court of her full brother, Ptolemy-II-King-of-Egypt-not-to-be-confused-with-any-of-the-other-Ptolemys-listed-herein.

But Ptolemy Keraunos did not live to enjoy his throne for very long. In 280 B.C., a group of barbarian tribes began raiding Thrace. The Thunderbolt was captured and killed while fighting them the next year.

20

ANTIOCHUS IV EPIPHANES

Why We “Draw the Line”

(CA. 215–164 B.C.)

After reading [the senate decree] through [Antiochus] said he would call his friends into council and consider what he ought to do. Popilius, stern and imperious as ever, drew a circle round the king with the stick he was carrying and said, ‘Before you step out of that circle give me a reply to lay before the senate.’ For a few moments he hesitated, astounded at such a peremptory order, and at last replied, ‘I will do what the senate thinks right.’ Not till then did Popilius extend his hand to the king as to a friend and ally.

—Livy, Roman historian

Gotta love this guy: a propagandist of the first order, his years in Rome had impressed him with the futility of fighting that resourceful people and of the importance of staying on their good side. A usurper (no surprise, considering how many Hellenistic monarchs were), he stole the throne from a nephew he later murdered after first marrying the boy’s mother. Antiochus was remembered by the ancient Hebrews as the evil king whose coming was predicted by their prophet Daniel.

Antiochus was the son of Antiochus III, who ruled the Seleucid Empire (which included parts of present-day Syria, Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Pakistan). Our Antiochus spent many years as a political hostage to the Roman Republic after a peace treaty between the two countries was established. After his father died, Antiochus’s older brother, Seleucus IV, succeeded to the throne. Antiochus was recalled from Rome, while Seleucus’s older son was sent there as a more appropriate political hostage from the new king. When Seleucus was murdered, his older son was still in Rome. Antiochus took the opportunity to seize the throne, at first calling himself co-ruler. A few years later, he got around to murdering his nephew.

After consolidating his power base, Antiochus went to war with the much weaker neighboring kingdom of Egypt, all but conquering it before being confronted by the Roman ambassador, Popilius, who demanded that Antiochus withdraw from Egypt or face war with the Roman Republic. This is the source of the adage of “drawing a line in the sand” (as laid out in the quotation that opens this chapter). Antiochus did not step over the line, but retreated from Egypt.

What’s in a Bastard’s Name?

The third son of Antiochus III (the Great), Antiochus seized power after his brother Seleucus was murdered in 175 B.C. Looking to strengthen his claim to the throne, Antiochus married his brother’s widowed queen, his own sister Laodice (the third of her own brothers she was forced to marry, and to whom she bore children!). He also hit on the idea of calling himself “Antiochus Epiphanes,” which in Greek literally means, “Antiochus, the actual manifestation of God on Earth.” Because he was a bit of a nut, many of his subjects took to calling him (behind his back) “Antiochus Epimanes,” a play on his chosen nickname that means “Antiochus the Crazy.”

By this time broke and really pissed off, Antiochus decided to loot the city of Jerusalem and its venerable temple on his way home to Syria. In his eyes, it was merely a way of catching the Hebrews up on their back taxes. The Hebrews didn’t see it that way, and when rioting ensued, Antiochus made the serious mistake of trying to suppress the Jewish religion.

The reasonably foreseeable result was the famous Maccabean uprising. You may have heard of a traditional celebration called Hanukkah? Commemorates the rededication of the temple after Judah Maccabee kicked the Seleucid king’s butt? This is that.

Later Seleucid kings agreed to allow the Hebrews their religious freedom and limited political autonomy. By that time, Antiochus had kicked off himself, dying suddenly while fighting rebels in Iran.

21

PTOLEMY VIII EURGETES

What Your Subjects Call You Behind Your Back Is a Lot More Important Than What They Call You to Your Face

(CA. 182–116 B.C.)

The Alexandrians owe me one thing; they have seen

their king walk!

—Scipio Aemilianus, Roman politician and general

That’s right, another Ptolemy. But where the first of our Ptolemaic bastards was ruthless and shrewd, and the second was brave, intemperate, and violent, our third was a gluttonous monster who celebrated one of his marriages by having his new stepson assassinated in the middle of the wedding feast, and later murdered his own son by this same woman (his sister!) in a brutal and sadistic fashion.

A younger son of Ptolemy V, who didn’t do the Ptolemaic dynasty any favors, this Ptolemy bounced around from Egypt to Cyprus to Cyrenaica (Libya) until his older brother (also a Ptolemy) died in 145 B.C. The dead Ptolemy’s young son was crowned shortly after his father’s death (taking the regnal name of Ptolemy VII) with his mother, Cleopatra II—no, not that Cleopatra—as co-ruler. In short order, our Ptolemy manipulated the common people into supporting him as king in place of his nephew, and managed to work out a compromise with his sister-also-his-brother’s-widow wherein he married her and the three of them became co-rulers of Egypt.

Not only did Ptolemy then promptly have his nephew (and now stepson) killed at the aforementioned wedding feast, he seduced and married as his second wife the boy’s sister, who also happened to be his own niece, and his wife’s daughter (confused yet?), also named Cleopatra. (No, still not that Cleopatra.) This after knocking up the sister/wife/widow of his dead predecessor herself, siring a son named Ptolemy (again) Memphitis.

When the people of Alexandria eventually rebelled and sent Ptolemy VIII, the younger Cleopatra, and their children packing to Cyprus, Cleopatra II (the sister/widow/first wife) set up their son Ptolemy Memphitis as co-ruler and herself (once more) as regent. Within a year, our Ptolemy (Ptolemy VIII, if you’re trying to keep track) had the boy, his own son, murdered. Pretty awful, right? Unspeakable?

No, that’s what came next.

Once he’d had the child (no older than twelve) killed, Ptolemy VIII had him dismembered and (no lie) sent to his mother as a birthday present!

As if this wasn’t enough, Ptolemy went on to retake his throne and share power with his first wife (yes, the sister/wife/widow whose sons he’d killed) until he died of natural causes after a long life in 116 B.C. Unspeakable bastard.

What’s in a Bastard’s Name?

When he took the throne of Egypt in 145 B.C., our Ptolemy took the reign name “Eurgetes” (Greek for “Benefactor”). In truth he was anything but. Quickly tiring of his lying, his murderous rages, and his rampant gluttony, his subjects began to refer to him as “Physcon” (“Potbelly”) because he was so fat. The quote that leads off this chapter references that physical characteristic as well as his laziness. Beholden to the Roman Republic for its support, Ptolemy VIII was forced to actually walk through the city of Alexandria (as opposed to being carted about in a litter) while playing tour guide to a visiting collection of Roman V.I.P.s, including Scipio Aemilianus, the author of the quote.

The Book of Ancient Bastards

The Book of Ancient Bastards